Major exhibition which was held, under this title, from October 8, 2011 to February 12, 2012 at the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Strasbourg then, from March 31 to July 15, 2012, at the Zentrum Paul Klee in Bern.

Full Text:

The major exhibition which was held, under this title, from October 8, 2011 to February 12, 2012 at the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Strasbourg then, from March 31 to July 15, 2012, at the Zentrum Paul Klee in Bern, is of interest to in more than one way anthropologists keen to exchange with art historians. Indeed, designed by Serge Fauchereau from a cultural history perspective bringing the arts and countries into dialogue, it invites us to explore two centuries of relationships between artistic practices and heterodox religious conceptions on a European scale. The works, known and less known, even ignored, come from Northern and Central Europe, France, Germany, Belgium, Switzerland, the two Iberian and Italian peninsulas, the United Kingdom and from Russia. The texts of the sumptuous catalog are signed by curators, art historians, writers, philosophers, historians of science brought together by the project manager who introduces at length all the sections with the exception of the last, devoted to experimentation scientist. “We cannot be satisfied with one art, in a country”, “we cannot separate those who associate”, likes to repeat Fauchereau who, after having taught American literature in the United States, learned from Pontus Hulten to visually implement this principle of influences, parallelisms and reciprocities between cultural centers and artistic languages in the major international exhibitions of the Georges-Pompidou center, during the 1970s-1980s: Paris–New York, Paris–Berlin , Paris–Moscow. But how can we transpose this principle, which has shown all its relevance for retracing the paths of invention of modernity, to a notion as indeterminate as that of the “occult”? “This exhibition focuses on the relationships of arts, literature and science with beliefs in the supernatural, magic and various forms of esotericism, from 1750 to 1950,” declares the designer who intends to to show the “negative of the Europe of the Enlightenment” (p. 68), its permanence and recompositions throughout the 19th century, finally its transpositions in the avant-garde movements until the end of surrealism. Ambitious, the idea is not entirely new.

Several exhibitions over the past twenty years have dealt with particular moments in this history. Magnetism and hypnotism were of course present in L’Âme au corps, art et sciences, 1793-1993, in 1993 at the Grand Palais, under the direction of Jean Clair and Jean-Pierre Changeux. Already included in the Trajectories of Dreams, from Romanticism to Surrealism, presented at the Pavillon des arts in 2003 under the direction of Vincent Gille, photographic demonstrations of spiritism and “psychic sciences” were at the center of the exhibition The Third Eye. Photography and the occult, co-produced in 2004 by the Metropolitan Museum in New York and the European House of Photography in Paris, under the direction of Clément Chéroux and Andreas Fischer. In 2006, Martin Myrone presented the two great English painters of the Gothic imagination at the Tate Britain: Gothic Nightmares: Fuseli, Blake and The Romantic Imagination. Finally, in 2009, we could see in Lille a visual history of the unconscious and its appropriations by the artistic avant-gardes: Hypnos. Images and unconscious in Europe (1900-1949), under the direction of Christophe Boulanger. The installation proposed by Fauchereau is first distinguished by its scale: nearly five hundred works are brought together to put these different moments into perspective, and more than three hundred books, documents and instruments compose, in a way, two secondary exhibitions at inside the museum space to combine pictorial, textual and experimental perspectives. But, as the texts signed by the art historian in the catalog show, these works are not only summoned to unfold a history of forms and thematic circulations. The ambition is to propose something like a history of religions renewed by the confrontation between the various pictorial, literary, architectural and musical expressions which have given a sensitive existence to heterodox cosmologies, from the point of view of Reason as well as from the point of view of view of the Churches. Has this project, which is exciting in itself, really been completed? Since Auguste Viatte’s major study on the importance of occultist and theosophical movements in the genesis of modern literature1, research has multiplied in all disciplines of the human sciences to restore the complexity of these metaphysical speculations as well as social forms and rituals.

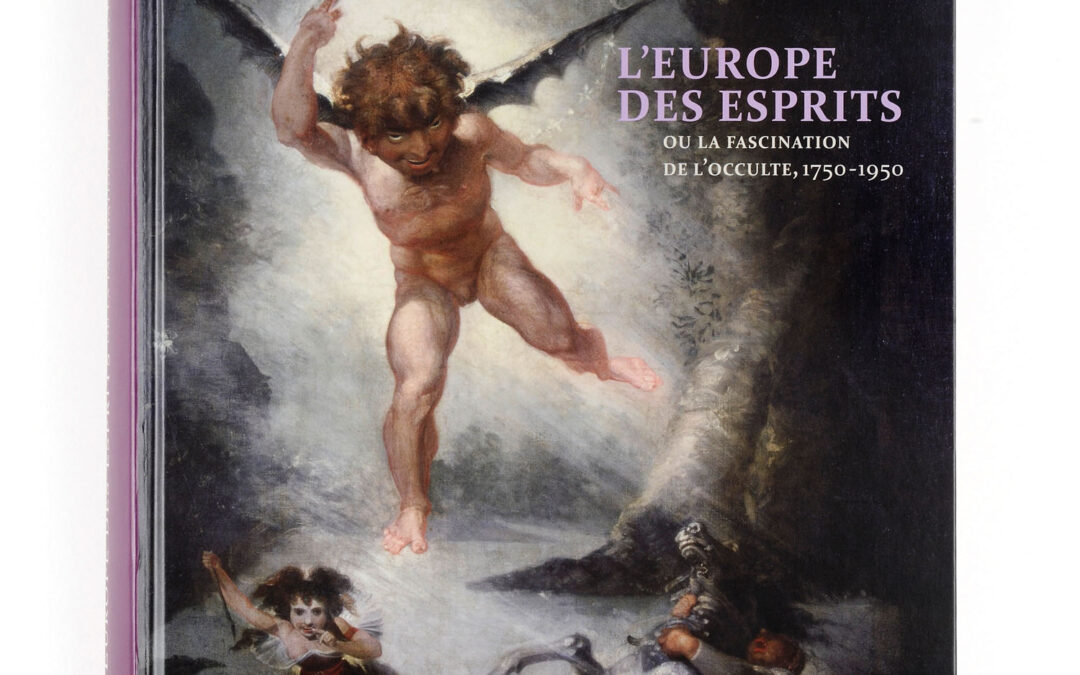

They are called to take care of them. The exhibition route begins with this pre-romanticism which saw a proliferation of affiliations to clubs, lodges and brotherhoods, which rewrote the Scriptures and encouraged aristocrats to communicate with angels and the dead by rereading ancient texts and putting themselves listening to the peasant voice. Appropriately, this fascination begins with Emanuel Swedenborg (1688-1772). The Swedish scientist first distinguished himself as a mathematician, before going through a long crisis which presented all the aspects of possession by the demonized dead; he freed himself from it in the manner of Christian mystics by a vision of Christ who established him as the messiah of a new faith. From 1745, the “prophet of the North” could, therefore, begin writing the eighteen volumes of his Celestial Arcana, to which would be added an intense apocalyptic production to announce the entry into the era of the new Jerusalem from the year 1757. Pre-Romanticism also gave rise to the Gothic novel with The Castle of Otranto: A Gothic History (1764) by Horace Walpole which, it is said, influenced Walter Scott and his numerous scenes of witches, ghosts and fairies. This inspiration is linked to Byron’s Manfred, which the painter Charles Durupt illustrated a little later by representing a magical apparition in his Manfred and the Spirit (1831). However, the journey which begins with the Romantics understands the relationship between painting and literature as essentially illustrative – as well as the treatment of Shakespearean characters and themes by artists as different as Richard Dadd, Johann Heinrich Füssli, Theodor von Holst, Théodore Chasseriau. The pride of place, of course, goes to Füssli, whose Robin Goodfellow-Puck (1787-1790), the leprechaun from Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, illustrates the cover of the catalog. But, to account for the links between painting and literature, is it enough to identify the motifs that circulate from books to paintings? Füssli, this “wild Swiss” who arrived in England on the eve of the birth of the Gothic novel, participated fully in this first English romanticism populated by witches, spirits and ghosts, who mixed horror and humor while being serious objects theological and legal debate. It is still necessary to remember that the centrality of the Shakespearean reference, far from being the sole particular interest of the artist, is widely sought after by a national construction enterprise of great authors. The project for a large illustrated edition of Shakespeare’s works, for which more than one hundred and fifty canvases were ordered from around thirty painters, gave rise to a multiplicity of competing commercial initiatives which employed painters and engravers2.

What repertoire of forms do we have, then, to make this plurality of beings from beyond “appear”? Are there iconographic codes available to distinguish various categories of apparitions – witches, spirits, specters, fairies and ghosts – and various categories of dream and visionary experiences? On this point, the works exhibited like the text signed by Fauchereau – “L’Europe de l’obscur” – leave the visitor and the reader equally bereft. Obviously, the way adopted to represent the sleeping beings of Queen Mab (1814) is no longer that of Titania’s Awakening (1785-1790), and the qualifier “mannerist lyricism” is quite insufficient to characterize changes in the figurative regime between a literary theme and its pictorial resumption within the artist’s singular trajectory. In the same way, we would wait for the series of Goya’s Caprices – including the famous The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters – to be commented not so much from the point of view of psychology or the critical posture of the artist, to decide whether or not the latter is under the influence of occult realities, as well as from the point of view of the figurative techniques used to produce an effect of fascination on the viewer’s gaze. If there are visual registers, and not just literary ones, of the fantastic, can we describe the figurative codes of this alliance of the probable and the improbable which makes it possible to produce, in the spectator, the impression of something below the represented, that is to say something impossible to represent? It is a shame that these questions of method which, among medievalist historians, opened the way to an anthropology of the medieval image – let us think of the work of Jean-Claude Schmitt born, precisely, from the Christian motif of The Pythoness of Endor making appearing before Saul the specter of Samuel – did not, it seems, modify the overall way of writing this cultural history. On the other hand, narrower studies which, based on a few examples, deal with philosophical or religious speculations, aesthetic theories and

expressive forms clearly show the impossibility of dissociating them for those who want to “read” drawings and paintings. The beautiful article that Roland Recht devotes to the singularity of German romanticism recalls the common ambition which links sciences, arts and beliefs: to grasp the universe not in the nostalgic mode of a lost totality but as a desire for a totality in the making. Visitors to the exhibition can admire a series of elegant engravings by the painter Philipp Otto Runge. They compose a cycle of the Hours where the principle of mystical unity of Nature, inspired by the botanical imagination of Goethe, is represented through a set of symmetrical compositions to be interpreted in symbolic key. Reading Recht we learn, moreover, that the artist intended to renew landscape painting to “make visible, with the help of color, divine Revelation” since the appearance on earth of blue, red and yellow are equivalent, according to him, to this revelation. Two other artists – Caspar David Friedrich and Carl Gustav Carus, painter and doctor – represent this German romanticism embodied by Faust where the landscape painting, shows the art historian, functions as an icon, that is to say like a “threshold”: it gives us access to “this beyond which is the represented landscape”. The second part of the exhibition, devoted to “symbolisms”, introduces lesser-known artists and works. Architectural utopias from all kinds of variations of theosophy rub shoulders with visual transpositions of Nordic mythologies. In France, the painter Paul-Élie Ranson’s interest in theosophy and spiritualism distinguishes him from the other nabis who meet in his studio: we can look at his Christ and Buddha, painted around 1890 incorporating Egyptian plant motifs, like the he figurative equivalent of this “eternal and universal religion” dreamed of by the Strasbourg resident Édouard Schuré in his vast fresco of the Great Initiates published in 1889, with the subtitle: Sketch of the secret history of religions. The work, which had immense success, intended to read in initiatory and prophetic key all the figures of founders of historical religions by adopting “the point of view of comparative esotericism”.

Laurence Perry traces the intellectual and spiritual trajectory of the writer whose abundant correspondence is preserved in the Strasbourg archives (p. 200-203). In Paris, a Salon de la Rose-Croix, a kabbalistic order created in 1888 by Stanislas de Guaïta and Joséphin Péladan, known as the Sâr Péladan, sets strict rules for the artists exhibited there: no scenes from contemporary life, no history paintings, no portraits, no realistic landscapes. Unlike Gustave Moreau and Odilon Redon, Carlos Schwabe agreed to exhibit there and designed the poster for the year 1892 while in England Yeats adhered to the Rosicrucian order of the Golden Dawn while doing ” Secret Rose” the motif of his poetic inspiration. For brief years, this movement, in France, also had its musician in the person of Erik Satie who composed Sonneries de la Rose-Croix for the opening of the Salon of 1892. Three years later, recalls Fauchereau, the musician would found his own “Metropolitan Art Church of Jesus Conductor.” But what powers does an artist recognize in art when he intends to fight society through the means of music and painting, within a “Church” of which he will never be anything other than the sole follower? Undoubtedly the anthropological notion of “religion of art” would make it possible to question the transfer of sacredness, and not of fascination for religion, even if heterodox, the commitment of a good number of artists gathered under the stylistic category of “symbolists.” This is the case, it seems to me, of all these Lithuanian and Estonian painters who often worked in Saint Petersburg – Boleslas Biegas, Rüdolfs Përle, Kristian Raud, Kazys Šimonis, Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis – and whose meeting in the exhibition constitutes a real discovery. Among them, the painter-musician Čiurlionis (1875-1911), originally from Lithuania, receives particular attention. During a long conversation with François Angelier, as part of the radio program “Mauvais genres”, Fauchereau recalled that when Vilnius airport reopened in 1990, he was on the first plane to go see the paintings of an artist whose approach seemed close to a Wassily Kandinsky or a Kazimir Malevich: “removing the figuration to keep only the colors and shapes which must mean in themselves3”.

The large number of his paintings presented in the exhibition responds to the text that Osvaldas Daugelis devotes, in the catalog, to the painter’s activity as a composer. The one that the critic Boris Leman described, in 1913, as the only a man worthy of being called a follower of the religion of the cosmos, but who refused to link his work to a theosophical inspiration, undertook in 1902 to translate his musical inspiration into pictorial compositions based on the analogy between the colors of the solar spectrum and the tones of the chromatic scale. The exhibition shows some of the painted works which, by their names, respond to each other like the movements of a sonata – Sonata du soleil, Allegro, Andante, Scherzo, Finale (1907) – as well as the entire cycle which transposes the signs of the zodiac in metaphysical landscapes (1906-1907). Misunderstood by his contemporaries in Vilnius, the unfinished cycle of The Creation of the World earned Čiurlionis the recognition of the Petersburg groups gathered around the magazines Le Monde de l’art and Apollon. After a stay in Saint Petersburg marked by material poverty and physical and psychological exhaustion, he died in 1911 in a psychiatric clinic near Warsaw. Let us add that recognition in Russia was established immediately after this premature death, but the war, then the revolution, contributed to the disappearance of the painter-musician engaged in the exploration of Lithuanian literature and popular songs from Russian culture. Only, in the mid-1920s, researchers gathered around the psychiatrist Pavel Karpov within the Academy of Artistic Sciences to question the relationship between creation and madness continued to be interested in his work, before Western art critics began to rediscover it in the 1970s and recognized its place in the transition to abstraction.

Art historian Christoph Wagner recalls the classic explanations for the birth of abstract art at the beginning of the 20th century – theory of relativity as a model for radical changes in worldview, new visualization and imaging devices, painting’s rivalry with photography and cinema – and the innovative demand to go back to the 18th century to identify a “prehistory” of abstract art. It is only relatively recently that art historians have recognized the relationships, sometimes very direct on the level of a history of ideas or personal cosmologies, between so-called esoteric doctrines and the various expressions of pre- guard. They constitute the third part where, alongside expected artists – Kandinsky, Malevitch, Piet Mondrian, Frantisek Kupka – appear less familiar authors, such as Jànos Mattis Teutsch, Janus de Winter and Wilhelm Morgner, who belong to the same movement of Blaue Reiter. However, recognizing the importance of theosophy for the birth of abstract painting does not consist of affirming the artists’ adherence to a religious prophecy governing the constitution of collectives subject to new rules of life. It is a question of contextualizing the worlds of reference and the patterns of thought which underlie the reflective work parallel to the technical work of experimenting with new expressive registers. In certain cases, this quest can be inscribed, in an imaginary way, in a cosmological thought, as attested by the title given by Kandinsky to a cycle of engravings, Small Worlds (1922), where the forms of composition by lines, dots and colors which “dematerialize” the painting are intended in analogy with the “compositions of nature”. But it is by virtue of the principle of synesthetic transposition that colors are assimilated to active entities. More disturbing is the reference to rare symbolic universes in a place that, until recently, had never been questioned from this angle: the Bauhaus art school, which has just made the the subject of a fascinating collective investigation led by Wagner4. Rationalism and functionality are not the only values that governed the research of this group to which, in 1919, Walter Gropius gave the program of “creating a new man”.

The art historian lists “the dizzying multiplicity” of the most divergent interests in matters of spirituality, lifestyle reforms and ordering of the world, with a notable presence of Zoroastrianism of which a community of practitioners is installed in Herrliberg, on the banks of the Walensee. This reference experienced during stays in this community is, in particular, the “iconological key” of the works of Johannes Itten, such as this calligraphic composition – Inspire, exhale (1922) – which transposes a maxim of Jakob Böhme to Zoroastrian knowledge (p. 261-263). A separate place is given to the Strasbourg artist Jean Arp, whose La Tête de lutin (1930) appears among other works nourished by a reflection on death. Finally, to the surrealist constellations the fourth part of this journey into the other side of the lights and into the nocturnal part of each of the great artistic movements that resulted from them is dedicated, with works by Max Ernst, André Masson, Joseph Šima – the painter of the Grand Jeu group –, Salvador Dali, Victor Brauner, and art brut. The few lines devoted to the group of Roger Gilbert-Lecomte, René Daumal and André Rolland de Renéville make us, once again, regret the absence of communication between art historians and anthropologists. “However strange they may be, their experiences are not exactly occult but relate to an alchemy of the spirit (they thus seek to get as close as possible to death),” writes Fauchereau (p. 293). To tell the truth, an ethnographic description of these very codified experiences of disruption of the senses has, in fact, no need to resort to the notion of the occult. It is a transposition, in the style of the seeing artist, of all these games of exploration, not of death, but of the border between the living and the dead necessary for the acquisition of masculinity in European companies5. We will be grateful to Annie Le Brun for having, in a beautiful article – “This ladder which leans on the wall of the unknown” –, insisted on the dimension of playful exploration of all the potentialities offered by the various divinatory techniques combined with this unique certainty, she writes, which animates the surrealist quest: “a definitive unbelief”. Not without humor, this journey through the multiple provinces of the other world offered by the exhibition ends with a bronze sculpture that Jacques Hérold created in 1947 at the request of André Breton, aptly named Le Grand “Transparent”.

Thus, from one period to another, the viewer is invited to follow the continuities and transformations of motifs and figures: for example, that of the witch and her metamorphosis into a spiritualist medium, or that of Isis, of which Fauchereau made a sort of common thread based on the study of Jurgis Baltrusaïtis, The Quest for Isis (1967). The metamorphosis of the witch into a spiritualist medium is more particularly covered by the two complementary exhibitions. A world of writings and images presents the treasures of the Cabinet des Estampes and the University Library of Strasbourg that Daniel Bornemann, curator of the reserves, has ordered by great civilizations and historical periods. This means that the disproportionate extension that the 19th century gave to the term “occult” by treating it as a noun is renewed, and not questioned. Some Mesopotamian tablets and Egyptian papyri stand alongside the translations of Marsilio Ficino and the Renaissance editions of the Sibylline oracles. The drawings and engravings which, from the 16th to the 20th century, illustrated The Divine Comedy, the great manuals of the Inquisition and the multiple treatises on the apparitions of angels and spirits from the 18th century correspond to the witches’ rides of Albert Dürer and the sabbats of Hans Baldung Grien or Marcantonio Raimondi who brought witchcraft into art, and the temptations of Saint Anthony engraved by Lucas Cranach and Jacques Callot. Can we assimilate such diverse social figures, symbolic logics and narrative or figurative genres to so many “speculations on the afterlife” and representations of the “upside down world”? On the other hand, the file collected on Cagliostro and the numerous works of Swedenborg, Ludwig Lavater, Louis-Claude de Saint-Martin, Karl Christian Kichner, Johan Kaspar Lavater and Heinrich Jung bear direct witness to the singular identity of Strasbourg, a crossroads city of all illuminist movements, groups and societies (p. 42), a city whose exhibition draws like a counter-history. The second exhibition, When science measured spirits, will teach nothing to spectators who saw, in 2004, the photographic materializations of spirits, of the deceased, of thoughts at the European House of Photography in Paris.

As for the articles in the catalog, they are content to summarize the analyzes of a cultural history of science and photography which persists in ignoring the questioning of anthropologists on the renewal of the experience of belief produced by photographic proof, inseparable of an exploration by the buyers of these images of the identity of the photographic sign as well as the places of solicitation, even negotiation, of an autobiographical story to rewrite the modern subject6. 15Seeing and seeing again, gathered in the same place, so many considerable works, scattered in museums across an entire continent, constitutes in itself an event. However, as evidenced by the perplexity of commentators, confronted with a dizzying undertaking whose richness, importance and ambition have all been praised, it is very difficult to adhere to one of the underlying theses, which Fauchereau has explained in the numerous interviews given to the press, namely the transhistorical continuity of “the belief in occult forces, benefic or evil… as old as humanity itself”. Does it not take us back to the theories of the origin of religion which fueled the anthropological debate more than a century ago? And, by giving the notion of occult such an indefinite extension, is this not depriving oneself of the means of proposing an overall interpretation of all the variations of a cultural upheaval which certain case studies presented here show us? wealth: the birth and diversified forms of a religion of art?