SPK were an Australian industrial and noise music group from the 1980s.

One of the members of the group Graeme Revell, then alone at the helm of this incredible musical project that came from nowhere, simply gave birth to the masterpiece of dark and ambient music: Zamia Lehmanni songs of the Byzantine Flowers.

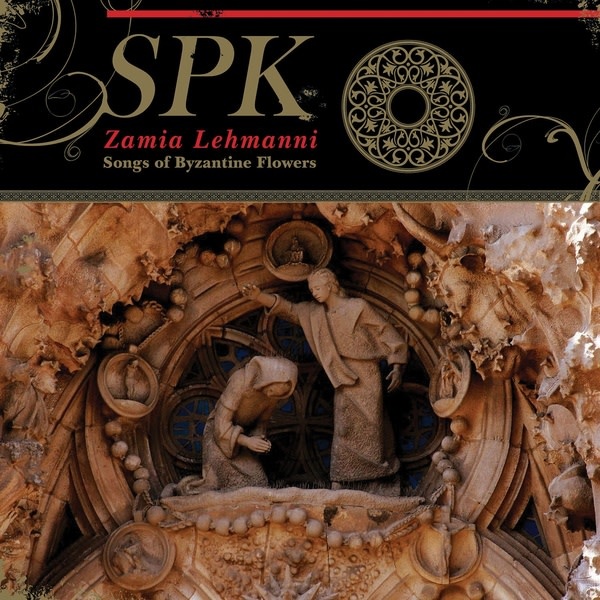

The theme is Byzantine culture (development of the Roman Empire at the end of the 4th century), and its influence on symbolist and decadent art, and on its subtleties and excesses. The album booklet is also full of quotes from authors such as Huysmans, Mallarmé, Baudelaire, Lautréamont and other Becketts, as if to signify the infinite extent of this culture… but this unique music is above all a true invitation to travel, to daydreaming. But by tortuous paths, as if the human soul had to go through its catharsis before finding serenity…

A timeless, organic and mystical masterpiece that many still consider THE benchmark, a profound and incredible mirage along the lost shores of history, culture and music. The aural intoxication of pungent and unforgettable scents of infernal exoticism.

“Pioneers of the industrial movement with Throbbing Gristle at the end of the 70s, the Australians of SPK share with the English group a preference for deconstruction, the manipulation of the masses by misappropriation of the media, human gangrene as a radical explanation for the ills of our time . Less overtly politicized but just as quick to use shocking images and slogans, SPK has been able to renew its musical approach with each demo or album, from the extreme noise of “Information Overload Unit” (1981) which anticipated the notion of power electronics to the tribal and post-punk flavors of “Auto-Da-Fé” (in fact a compilation of singles and unreleased releases, 1983), through one of the most important references of the genre, “Leichenschrei” (1982). From this diversity emerges a constant, that of striking minds with a non-conformist discourse and a socio-philosophical basis borrowing as much from Nietzche as from Bataille or Bachelard. However, the collective dissolved in 1983 and was immediately reborn as a single-headed entity under the leadership of Graeme Revell (now a film composer with some magnificent “scores” to his credit). Due to the times, electronics took over and joined forces with the dance floors and “Machine Age Voodoo” was released in 1984, a new wave flop which acted as an electric shock for those who expected a radicalization in response to the Reagan era. However Revell will surprise his world by cultivating the roots of dark ambient (even if Lustmord will develop them more significantly shortly after) with “Zamia Lehmanni”, a classy tangle of samples, religious songs, pads and “field recordings” and a mystical aura embalmed with 19th century fragrances (literary and historical quotations, influence of Byzantine culture on Romanticism and European Decadentism). Appropriately avoiding the mess that such a canvas could represent, the music oscillates between pure dark ambient and mystical impulses of the most beautiful effect, illustrating the mysteries of civilizations reconquered by literature, nature and its wonders (the zamia lehmanni, pride of Des Esseintes by Huysmans in “A Rebours”, is a pineapple of unusual proportions) and a numinous presence in each evocation/invocation which punctuates the journey of the pilgrim/listener, so much so that one could almost detect an analogy with the works of Dead Can Dance from the same period and above all a prefiguration of some of the flights of their “Serpent’s Egg”. Sinan’s singing radiates with its beauty and sadness on the fabulous “In Flagrante Delicto”, a sort of revisited Ave Maria whose strength still cannot be denied thirty years later. Timeless although full of references “Zamia Lehmanni” is what we call beyond any subject/object axiom a cornerstone of a building that is nevertheless fragile but over which the work of time has no influence. And if the 1992 CD version supervised by Lustmord (and published on a subdivision of Mute) offers a somewhat different mix, it pays one of the most beautiful tributes that can be to a masterpiece: remaining forever in a case that nothing and no one can defile.” (column originally published in Noise Magazine n°4, Feb/March 2008)